The Essential Guide to Canine Vaccines

This course will talk about how vaccines work and take you right through the nitty-gritty details including how reactions and responses happen, specific vaccine guidelines, duration of immunity, and everything you need to know about puppy vaccinations and alternatives!

- Tennis Ball Progress Bar - Shows you the percentage of the course you have completed

- Check Boxes - Click the check boxes to indicate completion of each course section

- Course Sections - Each section provides detailed information on one topic, making it easier for you to navigate and refer back to

- Arrows - Use the arrow buttons to open and close each course section

Getting Started

Modern veterinary medicine is becoming increasingly technologically advanced. Today's vets have much more sophisticated tools at their disposal than they did ten or twenty years ago. But as veterinary medicine progresses, one important aspect of veterinary medicine is being overlooked: immunology.

Veterinary immunologist, Dr Ronald Schultz PhD Dipl ACVIM, has addressed this gaping hole in veterinary medicine:

Our new grads don’t know a heck of a lot more about vaccines than our older grads. And I’ve figured out why this is. They know a lot more about basic immunology, but they don’t know about vaccinology and the two are not the same….Also, they’re taught by people generally that know nothing about vaccinology. Now, when do they get their vaccine training? During their fourth year. And who’s giving that? The veterinarians that know how to give vaccines, that still don’t know about vaccinology. So we haven’t gone very far from where we were ten years ago or twenty years ago with regard to training veterinarians about vaccines.

Today’s vets are stuck in a vaccination schedule that is dated and scientifically unproven. They are slow to adapt to the growing body of research showing that vaccines don’t need to be given as often as once though and that there are very real dangers associated with over-vaccination.

In the next section, we'll take a look at how the immune system can protect the body for a lifetime.

The Immune System - An Overview

Before discussing vaccination, it's important to have a fundamental understanding of the immune system.

Viruses like Parvovirus and Distemper are tiny organisms that are unable to reproduce on their own. They need a host cell to do this and they use cells in your dog's body to produce new viruses that infect even more cells. Often, the host cell is destroyed in the process.

Although it's

virtually impossible for viruses to enter the body through the skin, they can

make their way into the body through the eyes, nose and mouth. There is a

sticky mucus in these openings, as well as tiny hairs called cilia in the

respiratory tract that attack most foreign invaders. However some viruses can

make it past these primary defenses.

Although it's

virtually impossible for viruses to enter the body through the skin, they can

make their way into the body through the eyes, nose and mouth. There is a

sticky mucus in these openings, as well as tiny hairs called cilia in the

respiratory tract that attack most foreign invaders. However some viruses can

make it past these primary defenses.

When foreign intruders like bacteria or viruses enter the body, a part of the immune system quickly reacts and cells arrive at the site of the invasion. This triggers inflammation, which in turn attracts proteins that circulate in the blood. These proteins are capable of reacting directly with the antigen - the virus molecules that the body recognizes as foreign substances - and help immune cells find and "eat" the foreign invaders.

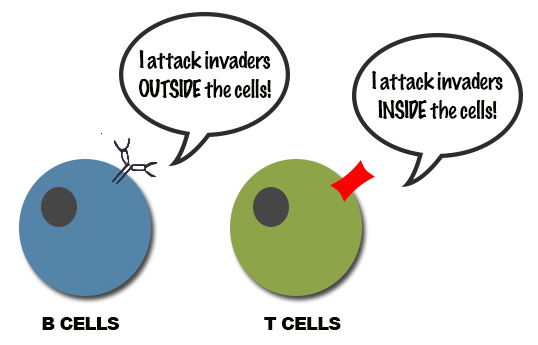

Lymphocytes: T Cells and B Cells

White

blood cells called lymphocytes are produced in bone marrow but migrate to the

lymphatic system, a transportation system that courses through the entire body

and feeds other parts of the lymphatic system (the lymph nodes, spleen and

thymus). The lymphatic system feeds the body's cells, filters out dead cells

and invades organisms like viruses and bacteria.

The surface of each lymphatic cell carries receptors that are capable of recognizing foreign substances. The lymphatic cells travel throughout the body, continuously searching for antigens.

T Cells

T cells come in two different types: helper cells and killer cells.

When specialized proteins eat foreign invaders, they then travel to the nearest lymph node. This in turn activates helper T cells, which begin to divide and produce proteins that activate B and killer T cells. The killer T cells specialize in attacking cells of the body that are infected with viruses. They use their specialized receptors to search every cell in the body for traces of antigen. If a cell is infected, it is swiftly killed.

B Cells

B cells also search for antigens in the body. When they find them, they connect to the antigen and use proteins produced by helper T cells to become fully activated. When this happens, the B cell will divide, creating two new cell types: plasma cells and B memory cells.

The Plasma Cell produces special proteins, called antibodies, that are released from the plasma cell so they can seek out foreign intruders and help destroy them. Plasma cells can release tens of thousands of antibodies per second.

When antibodies find an antigen, they neutralize toxins, incapacitate the virus and help eater cells called macrophages destroy the invader.

The Memory Cells are the second type of B cells. These cells have a long life span and are capable of "remembering" specific antigens and viruses. T cells can also produce longer-lived memory cells. The second time a virus tries to invade the body, B and T memory cells help the immune system to activate much quicker and the invaders are wiped out before the dog feels any symptoms. The dog now has permanent immunity against the invader.

In the next lesson, we’ll take a look at how vaccines create immunity.

How Vaccines Work Collapse

Vaccines contain either killed or live organisms that have been made less virulent. This process, called attenuation, allows vaccine manufacturers to add only a small amount of virus to the vaccine. To enhance the body's response to the small amount of virus, powerful immune stimulating substances such as aluminum and squalene are added to the vaccine. These are called adjuvants.

The combination of the attenuated virus and the adjuvants triggers an immune response by the body. This is similar to what would happen with natural infections - except there are a number of ways vaccination differs from natural immunity:

- Vaccines contain dangerous chemicals that have a toxic effect on the body.

- The route of entry is different than that of a naturally occurring disease. Most natural diseases would enter the body through the mouth or nasal cavity, not the skin.

- There is more than one disease present in most vaccines (typically from three to seven), whereas a dog would never naturally contract three or more diseases at the same time.

In the next section, we'll look at why this creates a problem.

Dangerous Vaccine Ingredients

A List Of Problematic Ingredients Collapse

A commonly overlooked aspect to vaccination is the potential risk it presents to the recipient. While vaccines can protect your dog from infectious disease, they are also capable of creating both acute reactions and chronic disease.

Here is a list of some of the problematic ingredients found in vaccines.

Bovine cow serum:

Extracted from cow skin. When injected causes connective tissue disorders, arthritis and lupus; also shortness of breath, low blood pressure, chest pain and skin reactions.

Sorbitol:

A synthetic sweetener that metabolizes very slowly and aggravates IBS and gastrointestinal issues.

Gelatin:

Derived from the collagen inside animals' skin and bones. Injecting gelatin poses the risk of infection from synthetic growth hormones and BSE infectivity (mad cow disease).

Sodium chloride:

Raises blood pressure and inhibits muscle contraction and growth.

Thimerosal:

A neurotoxic mercury which causes autism and cancer: the average human flu vaccine contains 10 times more mercury than the EPA safety limit, so dogs who are vaccinated with multiple vaccines can receive 30 to 70 times the safety limit of mercury in one day.

"Thimerosal is the preservative in immunization shots, so anytime you get an immunization shot you are undergoing the same procedure that in the University Lab we used to give animals auto-immune disease---give a little tiny injection of mercury.”

- Hal Huggins DDS

Formaldehyde:

Highly carcinogenic fluid used to embalm corpses. Ranked one of the most hazardous compounds to human health, it can cause liver damage, gastrointestinal issues, reproductive deformation, respiratory distress and cancer. formaldehyde has been known to fail to deactivate the virus the vaccine is intended to cure, thus enabling a live virus to infect the recipient.

Phenoxyethanol:

A glycol ether/chemical; highly toxic to the nervous system, kidneys, and liver. The FDA warns it "can cause shut down of the central nervous system (CNS), vomiting and contact dermatitis" when used topically.

Aluminum phosphate:

Greatly increases the toxicity of mercury, so the caution about minimum mercury tolerance is therefore severely underestimated. It can also cause degeneration of the brain and nervous system and neurological dysfunction, especially in developing puppies.

MSG:

Monosodium glutamate: When injected, it becomes a neurotoxin, causing CNS disorders and brain damage in children.

In the next section, we'll take a look at some studies showing the dangers of these ingredients.

Reports Of Vaccine Damage

A breakdown of studies Collapse

In 1991, a lab at the University of Pennsylvania documented a connection between an alarming increase in fibrosarcomas (a type of cancerous tumor) and vaccinations in cats. As it turns out, the mandatory annual rabies vaccinations led to an inflammatory reaction under the skin, which later turned malignant.

That same year, researchers at University of California at Davis confirmed that feline leukemia vaccines were also leading to sarcomas, even more so than the rabies vaccine. One in every thousand cats develop sarcoma every year.

In August 2003, the Journal of Veterinary Medicine carried an Italian study that showed that dogs also develop vaccine induced cancers at their injection sites.

In April 2010, an important scientific paper was published in the Journal of Virology. This paper showed how two teams of scientists in Japan and the UK isolated a feline retrovirus (called RD-114) in both feline and canine vaccines. This vaccine contamination came from vaccine seed stock, which is the disease shared amongst vaccine manufacturers internationally, from which they make their vaccines.

A team at Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine conducted several studies to determine if vaccines can cause changes in the immune system of dogs that might lead to life-threatening immune-mediated diseases. The results of the study showed that the vaccinated, but not the unvaccinated dogs, developed autoantibodies to many of their own biochemicals, including fibronectin, laminin, DNA, albumin, cytochrome C, cardiolipin and collagen.

In a 1989 study, Bari et al found autoimmunity to collagen in 72.4% of dogs with rheumatoid arthritis, 88% of dogs with infective arthritis and 52% of dogs with osteoarthritis. Dogs with cruciate disease also showed significantly increased levels of autoantibodies. They also had higher levels of anti-collagen antibodies in the synovial fluid (the fluid lining that surrounds joints). The researchers concluded that anti-collagen complexes were present in all joint disorders.

The link to cancer is known in human vaccines too. The Salk polio vaccine was reported to carry a monkey retrovirus (from cultivating the vaccine on monkey organs) that produces inheritable cancer. Years later, the monkey retrovirus SV40 still appears in human cancer sites.

Dr Larry Glickman, who spearheaded the Purdue research, concludes,

Our ongoing studies of dogs show that following routine vaccination, there is a significant rise in the level of antibodies dogs produce against their own tissues. Some of these antibodies have been shown to target the thyroid gland, connective tissue such as that found in the valves of the heart, red blood cells, DNA, etc.

It didn’t take many more findings like that before veterinary professionals began to consider vaccination as a risk factor in other serious autoimmune diseases. Vaccines were causing animals’ immune systems to turn against their own tissues, resulting in potentially fatal diseases such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia in dogs (AIHA). The vaccine manufacturer, Merck, states in The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy that AIHA may be caused by modified live-virus vaccines. This statement is also present in Tizard's Veterinary Immunology (4th edition) and the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Additional studies show that delayed vaccine reactions are the cause of thyroid disease, allergies, arthritis, tumors and seizures in both cats and dogs.

Although they are being removed from human biologic products, Thimerosal, mercury and aluminum based adjuvants are still being allowed in veterinary vaccines. These products are all potential antigens that could abnormally stimulate the immune system, last a lifetime and cause chronic disease.

It’s not hard to figure out that the more we vaccinate, higher the risk of autoimmune and other diseases in our dogs.

In the next section, we’ll look at the specific health issues vaccines can cause.

Adverse Vaccine Reactions

Autoimmune Disorders Collapse

Autoimmune disorders are the most common diseases seen in dogs today. Half of all adult dogs will get cancer, while significantly larger numbers suffer from autoimmune disorders such as allergies, hypothyroidism, arthritis and more.

Here are the most common adverse events caused by vaccines, according to Dr Ronald Schultz PhD Dipl ACVIM:

COMMON REACTIONS

Lethargy

Hair Loss, hair color change at injection Site

Fever

Soreness

Stiffness

Refusal to eat

Conjunctivitis

Sneezing

Oral ulcers

MODERATE REACTIONS

Immunosupression

Behavioral changes

Vitiligo

Weight loss (Cachexia)

Reduced milk production

Lameness

Granulomas/Abscesses

Hives

Faciale Edema

Atopy

Respiratory disease

Allergic uveitis (Blue Eye)

SEVERE REACTIONS

Vaccine

injection site sarcomas

Anaphylaxis

Arthritis, polyarthritis

HOD hypertrophy osteodystrophy

Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

Immune Mediated Thrombocytopenia (IMTP)

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (Neonatal Isoerythrolysis)

Thyroiditis

Glomerulonephritis

Disease or enhanced disease which the vaccine was designed to prevent

Myocarditis

Post vaccinal Encephalitis or polyneuritis

Seizures

Abortion, congenital anomalies, embryonic/fetal death, failure to conceive

These are the unfortunate risks pet owners assume when choosing to vaccinate. These risks make it critical to evaluate every vaccine that goes into our dogs, to make certain that no unnecessary vaccines are ever given.

In the next section, we’ll learn how foreign proteins in vaccines can cause allergies and autoimmune disease.

Autoimmunity and the Inflammatory Response to Vaccines Collapse

Disease micro-organisms are often cultured on animal tissue including embryonic chickens or cow fetuses. When a vaccine is manufactured, it’s impossible to divide the wanted virus from the unwanted animal tissue, so it all gets ground up together and injected into your dog’s body.

If a dog eats animal flesh or an egg, it is digested (broken down) into simpler amino acids before entering the bloodstream. The digestive process in most cases changes protein molecules so they don’t trigger an immune reaction.

When foreign animal protein is injected undigested, directly into the bloodstream, it immediately circulates throughout the body. When the body detects the presence of these foreign proteins, an immune response is triggered. Killer T cells are then sent out to consume the cells containing the foreign proteins and protein fragments.

Immunologist Tetyana Obukhanych PhD explains,

I believe that the exposure to yeast, egg, animal, or human proteins in the context of immunogenic (antibody producing) stimuli has the potential to result in sensitization to these proteins or even to break human immunologic tolerance to “self.” The latter is especially relevant to infants, since their immune system is only starting to make the distinction between “self” and “foreign.” Setting this distinction the wrong way from the start, in my view, is likely to pave the road to allergic or autoimmune manifestations.

In the next lesson, we’ll look at how vaccines can suppress the immune system.

Immune Suppression Collapse

The immune system is a finite resource and can only be stretched so far - so it is safest to avoid giving multiple antigens in one vaccine (Moore et al, JAVMA, 2005).

The Canine Adenovirus-2 (CAV-2) vaccine has been shown to cause immunosuppression in puppies for ten days after vaccination (Phillips et al, Can J Vet Res 1989), and the Parvovirus and Distemper vaccines have shown similar results

When vaccines are given in a combination shot, then the immunosuppression is compounded. Veterinary vaccines normally contain anywhere from three (Distemper-Adenovirus-Parvovirus) to seven components. Other vaccines like rabies, Lyme, leptospirosis or bordetella may also be given at the same time, resulting in even further immunosuppression.

Dr HH Fudenberg, a world renowned immunologist with hundreds of publications to his credit, comments

“One vaccine decreases cell-mediated immunity by 50%, two vaccines by 70%…all triple vaccines (Distemper-Adenovirus-Parvovirus) markedly impair cell-mediated immunity, which predisposes to recurrent viral infections, especially otitis media, as well as yeast and fungi infections.”

Similar results were also seen in the 2005 Purdue study referenced earlier. They found that the risk of reactions increased by 27 percent for each additional vaccine given per office visit in dogs under 22 pounds, and by 12 percent in dogs over 22 pounds.

Clearly, vaccination presents risks along with any benefits. In the next section, we’ll take a look at why dogs are over-vaccinated.

Why Dogs Are Over-Vaccinated

Revaccination Schedules Collapse

As we’ve learned, when animals (and humans) are exposed to disease naturally, the immune system is capable of creating a lifetime of protection by filing that information away in memory cells. It's very likely that vaccines offer the same duration of immunity.

But long term studies are expensive, so the vaccine manufacturers originally tested their products for only a few months and subsequently guaranteed their product to last a year.

Vets followed the vaccine label and began vaccinating annually, even though there was no science showing that vaccines needed to be given more than once or that vaccines provided a duration of immunity that was different than that from natural exposure to the disease. Vets also found that tying vaccines into annual visits got pet owners back into the clinic more often for annual checkups, and vets soon became comfortable with that schedule.

In the late 1970's immunologist Dr Ronald Schultz PhD Dipl ACVIM began research to show just how long those vaccines would actually last. The bulk of his testing was done on the core vaccines: Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus (DAP). Dr Schultz knew that the body had "memory cells" that were capable of detecting and deactivating infectious disease for life and he wanted to find out if vaccines were capable of stimulating those memory cells.

Over the next few decades, Dr Schultz tested over 1,000 dogs and tested every major brand of vaccine. He measured their immunity based on serology (measuring the amount of circulating antibodies), as well as challenge (exposing the dog to the actual virus, as would happen outside the lab).

Here are the results of his research:

Duration of Immunity for Core Vaccines

DISTEMPER

The Distemper vaccine for the Rockborn strain provides at least 7 years of protection while the Onderstepoort Strain provides at least 5 years of protection (this duration was shown with challenge studies; serology shows immunity lasts at least 9 to 15 years.

ADENOVIRUS

The Adenovirus vaccine provides at least 7 years of protection by challenge and at least 9 years of protection with serology.

PARVOVIRUS

The Parvovirus vaccine provides at least 7 years of protection by challenge and serology.

Dr Schultz's work clearly shows that vaccines last much longer than vets originally thought when they began vaccinating yearly. It's important to note that the above durations aren't necessarily how long the vaccines last, but rather the duration of the studies. Like natural infection, Dr Schtulz’s research shows that vaccines are extremely likely to provide many years, if not a lifetime, of protection.

In the next section, we'll take a look at how Dr Schultz’s work influenced today’s revaccination schedules.

Canine Vaccination Guidelines Collapse

In 2003, the American Animal Hospital Association Canine Vaccine Task Force evaluated the data from Dr Schultz’s challenge and serological studies and, while noting that the core vaccines had a minimum duration of immunity of at least seven years, compromised in 2003 with the statement that “revaccination every 3 years is considered protective.”

Task force member Dr Richard Ford, Professor of Medicine, North Carolina State University, said that the decision to recommend a three year revaccination schedule for core vaccines was a compromise.

“It’s completely arbitrary…,” he said. “I will say there is no science behind the three-year recommendation…”

Vets were comfortable with annual vaccination and many veterinary clinics relied on the income that annual vaccination generated, so getting them to move away from annual vaccination was proving difficult.

After the 2003 task force however, all of the major veterinary vaccine manufacturers completed their own studies showing a minimum three year duration of immunity on the core vaccines (Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus). So now vets could feel even more comfortable giving vaccines every three years or more, instead of annually.

Dr Schultz continued with his work and by 2006, had performed seven additional studies on over 1,000 dogs and repeated the same results, effectively showing that 95 to 98% of the dogs were protected for much longer than three years and most likely for life.

The Canine Vaccine Guidelines were updated again in February 2007 to update new information about Parvovirus and Distemper vaccination. Nearly thirty years after Dr Schultz’s initial research, the AAHA changed their revaccination recommendations for core vaccines to “revaccination every 3 years or more is considered protective.”

In the meantime, research was increasingly showing the deleterious effects of vaccines and this didn't escape the AAHA’s notice. In 2011, the AAHA updated their Canine Vaccination Guidelines once more. They advised that:

“Among healthy dogs, all commercially available [core] vaccines are expected to induce a sustained protective immune response lasting at least 5 yr. thereafter”

Back in 2003, the AAHA Task Force advised vets of the following in regard to their 3 year recommendation:

“This is supported by a growing body of veterinary information and well-developed epidemiological vigilance in human medicine that indicates immunity induced by vaccination is extremely long lasting and, in most cases, lifelong.”

While Dr Schultz’s work provides overwhelming evidence that the core vaccines can protect for at least seven years, and likely a lifetime, the veterinary associations have been slow to change their revaccination recommendations.

In the next section, we’ll learn how individual vets are responding to Dr Schultz’s work.

Why Dog Owners Need to Understand Duration of Immunity Collapse

Even though most major vaccine manufacturers have completed three year testing on their products, and the AAHA and AVMA state that the core vaccines can protect for at least five years, many vets are still vaccinating too often. In fact, the senior brand manager for vaccine manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim reports that 60% of vets are still vaccinating annually for the core vaccines.

The veterinary text book, Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy XI (Small Animal Practice), has this to say about annual vaccination on page 205:

A practice that was started many years ago and that lacks scientific validity or verification is annual revaccinations. Almost without exception there is no immunologic requirement for annual revaccination.

While many vets are vaccinating less often, the vast majority are still vaccinating too often. This is problematic because, although vaccines can protect companion animals from infectious disease, they are also capable of causing disease and ill health.

In the next section, we'll look at how to protect your dog with as few vaccines as possible.

How To Protect Your Dog With Fewer Vaccinations

Puppy Vaccination Schedules Collapse

When puppies are very young, they are protected from disease by ingesting their mother’s first milk, called colostrum. This rich milk contains maternal antibodies against disease, which the mother passes down to her puppies. The puppy’s immune system is not fully mature, or active, until around six months of age, but the maternal antibodies provide passive immunity to each puppy.

When a puppy with a reasonable amount of maternal antibodies is vaccinated, the maternal antibodies will essentially inactivate the vaccine, just as they would a real virus. In a study performed by Vanguard, researchers found that a combination vaccine (which typically contains Parvovirus, Distemper and one to five other antigens), given to six week old puppies had only a 52% chance of protecting them against Parvovirus.

This means that the puppy vaccinated at six weeks of age has 100% of the risk of the vaccine but only a 50% chance of being protected.

At nine weeks of age, 88% of the puppies in the study showed a response to the vaccine.

At 12 weeks, 100% of the puppies were protected. Some vaccines will provide protection earlier or later.

Dr Ronald Schultz has come to the following conclusion, based on his research:

“Only one dose of the modified-live canine ‘core’ vaccine, when administered at 16 weeks or older, will provide long lasting (many years to a lifetime) immunity in a very high percentage of animals.”

That very high percentage is 92% to 95% of dogs.

Vaccinating puppies under 12 weeks of age, and certainly under nine weeks of age is a high risk, low reward approach. Not only is the vaccine less likely to provide immunity, but it will also suppress the puppy’s immune system for ten days afterward.

Why Puppies (and Dogs) Don’t Need Boosters Collapse

Pfizer performed an interesting field study in 1996 where they split vaccinated puppies into two groups. Group A received a single vaccination at 12 weeks and Group B received a first vaccine between eight to 10 weeks, and a second at 12 weeks.

When titers were measured, 100% of the puppies vaccinated once at 12 weeks were protected whereas only 94% of the puppies in Group B were protected – despite receiving two vaccines as opposed to one.

It appears that the first vaccine can interfere with the second vaccine. So vaccinating your puppy twice not only doubles his risk for adverse vaccine reactions, it appears to make vaccination less effective overall.

Most people – and many vets – believe that it takes more than one vaccine to create immunity in a puppy. This simply isn’t true. It only takes one vaccine to protect a puppy, and if it is given at or after 16 weeks of age, it should protect him for life.

Maternal Antibodies

The only reason vets give puppies a series of vaccines is because they don’t know when the maternal antibodies will stop blocking the vaccine. The point in time when the maternal antibodies wane can vary between eight weeks and 26 weeks. So vets vaccinate every two to four weeks, trying to catch the window of opportunity when the maternal antibodies are low enough for the vaccine to work.

Most vets also vaccinate once more at a year of age – just to be certain. Nearly all vets vaccinate every year or three years after that – yet as Dr Schultz states, there is no need for revaccination once a puppy is protected – and if a puppy receives a vaccination at or after 16 weeks of age, he is very, very likely to be protected for at least seven years after, and likely for life.

Puppy Shots

Most vets vaccinate puppies every two to three weeks, because they have no way to tell whether the maternal antibodies have blocked the vaccine. We now know that the more vaccines we give our dogs, the more we expose them to mercury, aluminum and other toxins which are not only dangerous for the developing puppy’s neural system, but can be responsible for the common diseases we see in dogs today.

In place of revaccinating puppies at regular intervals, you can do two things to reduce the number of vaccines given to your puppy.

First, you can vaccinate only once at 16 weeks of age. Since we know that puppies vaccinated at this age are extremely likely to be protected for life, it would make the most sense to wait until this age to vaccinate. Since even vaccinated puppies should stay away from dog parks and other heavily trafficked areas (and the vet’s office should be included in this list), waiting until 16 weeks of age to vaccinate is a safe choice for most healthy puppies.

Shelters and Rescues

Many puppies are in high risk areas like shelters or rescues. Some puppies also come already vaccinated at 6 or 8 weeks of age. For puppies who are vaccinated at an earlier age, and even puppies vaccinated once at 16 weeks of age, titer tests can be invaluable.

In the next lesson, we’ll show you how this simple test can tell you if your dog needs another vaccination.

Non-Core Vaccines

Knowing The Difference Collapse

By Catherine O'Driscoll

Many of the vaccines vets use on your dog are categorized as core or non-core.

The core vaccines include parvovirus, distemper, adenovirus (canine hepatitis) and rabies. These vaccines all protect against viruses, which are easy to protect dogs against. In fact, viral vaccines are so effective that, when given to a dog over four months of age, they’ve been scientifically proven to protect that dog for years, and most likely for life.

The non-core vaccines aren’t in included in this group for three main reasons:

- They don’t work as well

- They don’t protect for very long

- They’re more dangerous

Leptospirosis Collapse

Leptospirosis

The majority of dogs with known leptospirosis have been found to be without symptoms – they live with it without getting ill.

This isn’t to say that leptospirosis can’t cause illness in dogs. In some cases lepto can be fatal.

However, in the 1996 Canine Health Concern vaccine survey 100% of dogs with leptospirosis had been vaccinated within three months prior to infection. This can only be because:

- The vaccine caused the disease, or

- The vaccine didn’t contain the serovar that caused the illness, or

- The vaccine contained a non-local serovar that the dog hadn’t adapted to, or it just didn’t work.

If your vet recommends a lepto shot, you need to ask him two questions. The first is whether he has seen a case of lepto in the last, say, six months (i.e., is the vaccine necessary?). The second is which serovar is involved, and is that serovar in the vaccine? For if it’s not, the vaccine won’t help. There are over 200 versions of leptospirosis and vaccination against one form will not provide protection against the others.

The WSAVA VGG states,

The leptospirosis vaccine is the one least likely to provide adequate and prolonged protection, and therefore must be administered annually or more often for animals at high risk. Protection against infection with different serovars is variable. This product is associated with the greatest number of adverse reactions to any vaccine.”

If you take time to understand the above advice, you’d have to conclude the vaccine doesn’t work and is dangerous. If something doesn’t work and is dangerous, why keep doing it?

The VGG adds,

Leptospira vaccines provide short-term immunity (e.g., 3–12 months) and the efficacy is often less than 70%. Also leptospira products often prevent clinical disease but fail to protect against infection and shedding of the bacteria, especially when infection occurs more than 6 months after vaccination. The immunity among the serovars varies and immunity varies among vaccinated dogs. Persistence of antibody after vaccination will often be only a few months and immunological memory for protective immunity is short (e.g. 1 year or less). Thus, revaccination may be required as often as every 6–9 months for dogs at high risk.”

So, in summary:

- The lepto vaccine doesn’t protect a third of dogs;

- It might not protect any if the form of lepto in your area is different to the form in the vaccine;

- An annually vaccinated dog can be unprotected for up to nine months of the year; and infected dogs – irrespective of vaccination – are hidden infective reservoirs, capable of spreading lepto to humans and other animals.

- And yet – despite all this – leptospirosis is still a very rare disease in most parts of the world. There are virtually no records of dogs passing lepto onto humans, and we don’t hear of dogs with lepto often.

No human vaccine is currently available in the United States or the UK for lepto. Why, do you think?

The Lancet, Infectious Diseases Vol 3 December 2003 might explain why:

Several problems confront the development of a vaccine to prevent human leptospirosis. First, an unacceptable side effect profile of killed bacterial vaccines has often been reported. Second, the killed bacteria vaccines are likely to provide only short-term and possibly incomplete protection, similar to that reported with anti-leptospiral vaccines in animals. Third, the locally varying patterns of Leptospira transmitted may preclude the development of a suitably generalisable vaccine. Fourth, there is theoretical potential for inducing autoimmune disease such as uveitis and, lastly, there is incomplete knowledge of mechanisms of protective immunity against leptospiral infection.”

The Lancet also stated: “Vaccination of animals such as dogs or cattle may prevent illness but not leptospiruria and hence transmission to human beings.”

Scientists have been trying to develop a human leptospirosis vaccine for decades – one that’s safe and effective and which governments will license around the world. They have failed.

But a dangerous, ineffective, substandard canine vaccine is out there, and will remain out there until pet owners educate themselves of the risks.

What is the leptospirosis vaccine doing on the WSAVA non-core list? It has no place there. It should be on the “not recommended” list. Leptospirosis is not even a vaccinatable disease, and the vaccine can kill!

Ask Alison Lovell what she thinks of this vaccine. Her beautiful GSD puppy was a perfectly normal little man the day before she was persuaded to give him the lepto shot. The day after he was brain dead, and the week after he was literally dead.

Ask Sue and Zoe Lewsley whose Champion Doberman, Tommy, experienced inflammation in his entire body after a lepto shot. Tommy was screaming in pain and couldn’t move. Within three months, despite extensive veterinary support, the nerve damage in Tommy’s body was so severe that he had to be put to sleep. An adverse vaccine event report was filed by Tommy’s vet.

But over 99% of vaccine reactions go unreported in dogs and cats.

Lyme Disease Collapse

Lyme Disease

As with leptospirosis, Lyme disease is also caused by a bacteria, but is transmitted through tick bites. Lyme disease exists in most states in America.

As with leptospirosis, not all dogs who test positive for Lyme disease suffer symptoms, and the disease can be treated with antibiotics or good holistic care.

The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM), stated in 2005, “The ACVIM diplomates believe the use of Lyme vaccines is still controversial and most do not administer them.” Neither do the American veterinary schools recommend the Lyme vaccine.

Dr Patricia Jordan writes,

In some cases, dogs develop Lyme disease despite the vaccine, or maybe because of the vaccine. Research dogs develop all the symptoms of Lyme disease up to six weeks after receiving the shot, while tests for the Lyme disease bacteria show up as negative. Left untreated more concerning issues develop.”

Cornell University’s School of Veterinary Medicine researchers suspect long-term side effects are associated with the Lyme disease vaccine for dogs, but nothing definitive has been documented or exhaustively studied, says Allen Schoen, a doctor of veterinary medicine in Sherman, Connecticut. “These side effects may vary from rheumatoid arthritis and all the major symptoms of Lyme disease to acute kidney failure.”

There is some controversy about how long a tick must be on your dog before it injects the Borrelia bacterin that causes Lyme disease into him. Some say five hours, others say up to 70 hours. Therefore the safest and most effective “vaccine” would be to inspect your dogs daily and remove ticks before they attach, or as quickly as possible.

Other preventative measures include keeping your lawn short, not feeding wildlife near your garden and using other non-toxic forms of tick preventation.

Given the evidence, it is difficult to imagine why the Lyme vaccine isn’t on the “not recommended” list.

Kennel Cough Collapse

Kennel Cough

Kennel cough is caused by a variety of agents including – but not limited to – parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, and the Bordetella bronchiseptica bacterin.

The WSAVA informs us that,

It is important to realize that not all members of the Kennel Cough complex have a vaccine. Also, because Kennel Cough is a localized infection (meaning it is local to the respiratory tract), it is an infection that does not lend itself to prevention by vaccination.”

Putting this is plain English, the WSAVA seems to be saying that kennel cough vaccines don’t work, or that kennel cough is not a vaccinatable disease.

Most combination canine vaccines contain injectable parainfluenza as well as adenovirus, expressed as ‘DHPPi = (D) Distemper, (H) Hepatitis/adenovirus, (P) Parvovirus and (Pi) Parainfluenza.

The Bordetella bronchiseptica vaccine is a live avirulent bacteria, given up the nose. It’s generally combined with intranasal parainfluenza. The WSAVA advises that “the Bordetella vaccine may promote transient (3–10 days) coughing and sneezing, and nasal discharge may occur in a small percentage of vaccinates.”

The implication of this, is (and the evidence suggests), that kennel cough vaccines cause kennel cough outbreaks.

Alison Hunt of the Tor View Kennels wrote to me, “We have just had a kennel cough case, meaning our workload goes into overdrive to isolate/disinfect even more. I’ve now found out that her owners were persuaded to have ‘up the nose’ drops on the 4th. The bitch came to us on the 16th, and started it all on the 26th.

“You can imagine the explanations and advice we’ve had to give to every other owner. It’s very time consuming. Hopefully we have controlled things, cordoning off areas, the staff spraying themselves, and so on. We’re taking a mass of precautions. Thankfully we’ve only had two cases, which we’ve been treating. We’ve also given the kennel cough nosode to every incomer.”

Although kennel cough is not a serious disease for the majority of dogs, it’s a serious disease for kennel owners. Their reputation and livelihood can be irrevocably damaged by vaccine-induced kennel cough outbreaks.

In its Guidelines document, the WSAVA states:

Certain vaccines have a higher likelihood of producing adverse reactions, especially reactions caused by Type I hypersensitivity. For example, bacterins (killed bacterial vaccines), such as Leptospira, Bordetella (kennel cough), Borrelia (Lyme disease) and Chlamydophila are more likely to cause these adverse reactions than MLV viral vaccines.”

Type I hypersensitivity reactions involve an immune mediated reaction that releases potent inflammatory mediators and other chemicals that trigger an anaphylactic reaction in the affected animal. The reactions are usually acute, with the clinical signs appearing within minutes or hours of vaccination. Typical signs reported are facial oedema, shock, lethargy, respiratory distress and diarrhoea. Severe anaphylactic reactions may result in death. Urticaria (hives), facial edema and anaphylactic shock are specific clinical manifestations of Type I hypersensitivities.

Ann wrote to me to tell me what happened to her dog Yogi, when he received a kennel cough vaccine. On the night of the vaccine, he was lethargic and quiet, hiding out in his kennel. The next day he was struggling to breathe and panicking, and an x-ray revealed an inflamed and collapsed windpipe. A battery of tests costing £2,500 revealed no known cause, although the vaccine manufacturer offered £1,000 towards the bill. Ann told them where to stick their offer, feeling that they should be held responsible for the entire bill.

Once again, there is compelling evidence to suggest that kennel cough vaccines should not even be on the non-core list. Kennel cough is a transient disease and the vaccine causes outbreaks and risks more serious adverse reactions.

The only positive benefit for its existence is that it keeps booster income flowing for vets.

Intelligent Revaccination

What Is Titer Testing? Collapse

As we’ve learned, when dogs are exposed to viruses, the immune system responds by sending out circulating antibodies and then producing long-lasting memory cells. Fortunately, there is a simple blood test your vet can perform to determine whether your dog’s vaccine has protected him or whether he needs another.

A titer test (pronounced TIGHT-er) is a laboratory test measuring the existence and level of antibodies to vaccine viruses and other infectious agents. As we’ve learned, antibodies are produced when an antigen (like a virus or bacteria) provokes a response from the immune system. This response can come either from natural exposure or from vaccination. Titers are also called serum vaccine antibody titers and serologic vaccine titers.

How Is The Test Performed? Collapse

Your vet will draw blood to perform a titer test. The blood sample is then diluted. Titer levels, expressed as ratios, indicate how many times blood can be diluted before no antibodies are detected. If blood can be diluted 1000 times and still show antibodies, the ratio would be 1:1000. This is a “strong” titer. A titer of 1:2 would be weak.

FYI

Titer tests are readily available for the core (Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus) vaccines. They can be sent by your vet to diagnostic labs (Hemopet offers cost effective testing), or done right in the veterinary office with an in-house test like Vaccicheck.

If any amount of titer is present, it indicates that your dog or puppy has adequate immunity. A positive titer means you don’t need to introduce unnecessary vaccines and the harmful adjuvants, preservatives and foreign animal proteins to your dog. You can skip the next vaccine and know that your dog or puppy is protected, and likely for life.

If you fear that your dog’s protection might not last as long as Dr Schultz’s research indicates, you can choose to have your vet run another titer test every three years or so instead of vaccinating. Most pet owners who do this find that their dogs carry sufficient titers throughout their life and never have to be revaccinated.

In the next section, we’ll take a look at some limitations titers present.

The Limitations of Titer Testing Collapse

Titering puppies two to three weeks after vaccination is a sound strategy. During this period, circulating antibodies should be elevated in response to the vaccine. If they aren’t then it’s highly likely the puppy has not responded to the vaccine and should be revaccinated, preferably only for the one virus that shows a low titer. There is no point in vaccinating with a multivalent (containing more than one virus) vaccine if he is only low on Parvovirus.

Titering adult dogs is less straightforward. Although positive titers are strongly predictive of protection, negative titers present a challenge. Because titers measure only circulating antibodies and not the backbone of immunity, the memory cells, negative titers don’t necessarily mean your dog is unprotected. This is a shortfall of titer testing. However, knowing that 92 to 98% of dogs vaccinated after 16 weeks of age are protected for life, dog owners can feel comfortable knowing their dog is protected if they have previously shown a protective titer, even if their titer is now negative.

Veterinary Acceptance of Titer Testing Collapse

Just as vets are slow to adapt to Dr Schultz’s duration of immunity research, they are equally slow to adopt titer testing in lieu of revaccination. Some believe this testing is too costly while others incorrectly believe titer tests aren’t a valid method of evaluating immunity.

Dr Jean Dodds states, “With all due respect to these professionals, this represents a misunderstanding of what has been called the “fallacy of titer testing,” because research has shown that once an animal’s titer stabilizes, it is likely to remain constant for many years. Properly immunized animals have sterilizing immunity (immunity that prevents further infection even when an animal is exposed) that not only prevents clinical disease but also prevents infection, and only the presence of antibody can prevent infection.”

“Furthermore, protection as indicated by a positive titer result is not likely to suddenly drop off unless an animal develops a severe medical condition or has significant immune dysfunction. It’s important to understand that viral vaccines prompt an immune response that lasts much longer than the immune response elicited by contracting the actual virus. Lack of distinction between the two kinds of responses may be why some practitioners think titers can suddenly disappear.”

Dr Ronald Schultz offers the following on the value of vaccine titer testing, “You should avoid vaccinating animals that are already protected, and titer testing can determine if adequate, effective immunity is present. It is often said that the antibody level detected is 'only a snapshot in time.’ That’s simply not true; it is more a 'motion picture that plays for years.’ ”

Your Better Understanding = Better Protection For Your Dog

Summary Collapse

Because vets have been slow to adapt to newer research showing long lasting immunity and the deleterious effects of vaccination, the onus is on you as a dog owner to understand the immune system and how to protect your dog not only from infectious diseases, but also from vaccine-induced and autoimmune diseases.

This guide should give you the tools you need to work with your vet to reduce the number of unnecessary vaccines your dog receives – or to find a vet who is more open to this research.

It is also possible to avoid vaccination altogether. Some pet owners would rather assume the risk of infectious disease like Parvovirus than the risk of cancer or other diseases that can impact both the quality and length of life of their companion animals. Titer testing unvaccinated animals often shows protective levels and is a testament to the power of the immune system in healthy dogs fed a high quality diet.

Understanding the science behind vaccination is a first and vital step toward providing your dog or puppy a better chance at good health.

Please Note: This course discusses only the core vaccines: Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus. Although Rabies vaccination has shown a similar duration of immunity, it is required by law in all states and some provinces. Non-core vaccines like Bordetella, Lyme and Leptospirosis are bacterin vaccines and have a very different impact on the immune system. Lyme and Leptospirosis vaccines are also reported to present a higher risk to dogs and are less likely to protect than the core vaccines, which is why there are considered non-core vaccines.

Bottom of Form

Although it's virtually impossible for viruses to enter the body through the skin, they can make their way into the body through the eyes, nose and mouth. There is a sticky mucus in these openings, as well as tiny hairs called cilia in the respiratory tract that attack most foreign invaders. However some viruses can make it past these primary defenses.

When foreign intruders like bacteria or viruses enter the body, a part of the immune system quickly reacts and cells arrive at the site of the invasion. This triggers inflammation, which in turn attracts proteins that circulate in the blood. These proteins are capable of reacting directly with the antigen - the virus molecules that the body recognizes as foreign substances - and help immune cells find and "eat" the foreign invaders.

Lymphocytes: T Cells and B Cells

White

blood cells called lymphocytes are produced in bone marrow but migrate to the

lymphatic system, a transportation system that courses through the entire body

and feeds other parts of the lymphatic system (the lymph nodes, spleen and

thymus). The lymphatic system feeds the body's cells, filters out dead cells

and invades organisms like viruses and bacteria.

The surface of each lymphatic cell carries receptors that are capable of recognizing foreign substances. The lymphatic cells travel throughout the body, continuously searching for antigens.

T Cells

T cells come in two different types: helper cells and killer cells.

When specialized proteins eat foreign invaders, they then travel to the nearest lymph node. This in turn activates helper T cells, which begin to divide and produce proteins that activate B and killer T cells. The killer T cells specialize in attacking cells of the body that are infected with viruses. They use their specialized receptors to search every cell in the body for traces of antigen. If a cell is infected, it is swiftly killed.

B Cells

B cells also search for antigens in the body. When they find them, they connect to the antigen and use proteins produced by helper T cells to become fully activated. When this happens, the B cell will divide, creating two new cell types: plasma cells and B memory cells.

The Plasma Cell produces special proteins, called antibodies, that are released from the plasma cell so they can seek out foreign intruders and help destroy them. Plasma cells can release tens of thousands of antibodies per second.

When antibodies find an antigen, they neutralize toxins, incapacitate the virus and help eater cells called macrophages destroy the invader.

The Memory Cells are the second type of B cells. These cells have a long life span and are capable of "remembering" specific antigens and viruses. T cells can also produce longer-lived memory cells. The second time a virus tries to invade the body, B and T memory cells help the immune system to activate much quicker and the invaders are wiped out before the dog feels any symptoms. The dog now has permanent immunity against the invader.

In the next lesson, we’ll take a look at how vaccines create immunity.

How Vaccines Work Collapse

Vaccines contain either killed or live organisms that have been made less virulent. This process, called attenuation, allows vaccine manufacturers to add only a small amount of virus to the vaccine. To enhance the body's response to the small amount of virus, powerful immune stimulating substances such as aluminum and squalene are added to the vaccine. These are called adjuvants.

The combination of the attenuated virus and the adjuvants triggers an immune response by the body. This is similar to what would happen with natural infections - except there are a number of ways vaccination differs from natural immunity:

- Vaccines contain dangerous chemicals that have a toxic effect on the body.

- The route of entry is different than that of a naturally occurring disease. Most natural diseases would enter the body through the mouth or nasal cavity, not the skin.

- There is more than one disease present in most vaccines (typically from three to seven), whereas a dog would never naturally contract three or more diseases at the same time.

In the next section, we'll look at why this creates a problem.

Dangerous Vaccine Ingredients

A List Of Problematic Ingredients Collapse

A commonly overlooked aspect to vaccination is the potential risk it presents to the recipient. While vaccines can protect your dog from infectious disease, they are also capable of creating both acute reactions and chronic disease.

Here is a list of some of the problematic ingredients found in vaccines.

Bovine cow serum:

Extracted from cow skin. When injected causes connective tissue disorders, arthritis and lupus; also shortness of breath, low blood pressure, chest pain and skin reactions.

Sorbitol:

A synthetic sweetener that metabolizes very slowly and aggravates IBS and gastrointestinal issues.

Gelatin:

Derived from the collagen inside animals' skin and bones. Injecting gelatin poses the risk of infection from synthetic growth hormones and BSE infectivity (mad cow disease).

Sodium chloride:

Raises blood pressure and inhibits muscle contraction and growth.

Thimerosal:

A neurotoxic mercury which causes autism and cancer: the average human flu vaccine contains 10 times more mercury than the EPA safety limit, so dogs who are vaccinated with multiple vaccines can receive 30 to 70 times the safety limit of mercury in one day.

"Thimerosal is the preservative in immunization shots, so anytime you get an immunization shot you are undergoing the same procedure that in the University Lab we used to give animals auto-immune disease---give a little tiny injection of mercury.”

- Hal Huggins DDS

Formaldehyde:

Highly carcinogenic fluid used to embalm corpses. Ranked one of the most hazardous compounds to human health, it can cause liver damage, gastrointestinal issues, reproductive deformation, respiratory distress and cancer. formaldehyde has been known to fail to deactivate the virus the vaccine is intended to cure, thus enabling a live virus to infect the recipient.

Phenoxyethanol:

A glycol ether/chemical; highly toxic to the nervous system, kidneys, and liver. The FDA warns it "can cause shut down of the central nervous system (CNS), vomiting and contact dermatitis" when used topically.

Aluminum phosphate:

Greatly increases the toxicity of mercury, so the caution about minimum mercury tolerance is therefore severely underestimated. It can also cause degeneration of the brain and nervous system and neurological dysfunction, especially in developing puppies.

MSG:

Monosodium glutamate: When injected, it becomes a neurotoxin, causing CNS disorders and brain damage in children.

In the next section, we'll take a look at some studies showing the dangers of these ingredients.

Reports Of Vaccine Damage

A breakdown of studies Collapse

In 1991, a lab at the University of Pennsylvania documented a connection between an alarming increase in fibrosarcomas (a type of cancerous tumor) and vaccinations in cats. As it turns out, the mandatory annual rabies vaccinations led to an inflammatory reaction under the skin, which later turned malignant.

That same year, researchers at University of California at Davis confirmed that feline leukemia vaccines were also leading to sarcomas, even more so than the rabies vaccine. One in every thousand cats develop sarcoma every year.

In August 2003, the Journal of Veterinary Medicine carried an Italian study that showed that dogs also develop vaccine induced cancers at their injection sites.

In April 2010, an important scientific paper was published in the Journal of Virology. This paper showed how two teams of scientists in Japan and the UK isolated a feline retrovirus (called RD-114) in both feline and canine vaccines. This vaccine contamination came from vaccine seed stock, which is the disease shared amongst vaccine manufacturers internationally, from which they make their vaccines.

A team at Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine conducted several studies to determine if vaccines can cause changes in the immune system of dogs that might lead to life-threatening immune-mediated diseases. The results of the study showed that the vaccinated, but not the unvaccinated dogs, developed autoantibodies to many of their own biochemicals, including fibronectin, laminin, DNA, albumin, cytochrome C, cardiolipin and collagen.

In a 1989 study, Bari et al found autoimmunity to collagen in 72.4% of dogs with rheumatoid arthritis, 88% of dogs with infective arthritis and 52% of dogs with osteoarthritis. Dogs with cruciate disease also showed significantly increased levels of autoantibodies. They also had higher levels of anti-collagen antibodies in the synovial fluid (the fluid lining that surrounds joints). The researchers concluded that anti-collagen complexes were present in all joint disorders.

The link to cancer is known in human vaccines too. The Salk polio vaccine was reported to carry a monkey retrovirus (from cultivating the vaccine on monkey organs) that produces inheritable cancer. Years later, the monkey retrovirus SV40 still appears in human cancer sites.

Dr Larry Glickman, who spearheaded the Purdue research, concludes,

Our ongoing studies of dogs show that following routine vaccination, there is a significant rise in the level of antibodies dogs produce against their own tissues. Some of these antibodies have been shown to target the thyroid gland, connective tissue such as that found in the valves of the heart, red blood cells, DNA, etc.

It didn’t take many more findings like that before veterinary professionals began to consider vaccination as a risk factor in other serious autoimmune diseases. Vaccines were causing animals’ immune systems to turn against their own tissues, resulting in potentially fatal diseases such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia in dogs (AIHA). The vaccine manufacturer, Merck, states in The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy that AIHA may be caused by modified live-virus vaccines. This statement is also present in Tizard's Veterinary Immunology (4th edition) and the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine.

Additional studies show that delayed vaccine reactions are the cause of thyroid disease, allergies, arthritis, tumors and seizures in both cats and dogs.

Although they are being removed from human biologic products, Thimerosal, mercury and aluminum based adjuvants are still being allowed in veterinary vaccines. These products are all potential antigens that could abnormally stimulate the immune system, last a lifetime and cause chronic disease.

It’s not hard to figure out that the more we vaccinate, higher the risk of autoimmune and other diseases in our dogs.

In the next section, we’ll look at the specific health issues vaccines can cause.

Adverse Vaccine Reactions

Autoimmune Disorders Collapse

Autoimmune disorders are the most common diseases seen in dogs today. Half of all adult dogs will get cancer, while significantly larger numbers suffer from autoimmune disorders such as allergies, hypothyroidism, arthritis and more.

Here are the most common adverse events caused by vaccines, according to Dr Ronald Schultz PhD Dipl ACVIM:

COMMON REACTIONS

Lethargy

Hair Loss, hair color change at injection Site

Fever

Soreness

Stiffness

Refusal to eat

Conjunctivitis

Sneezing

Oral ulcers

MODERATE REACTIONS

Immunosupression

Behavioral changes

Vitiligo

Weight loss (Cachexia)

Reduced milk production

Lameness

Granulomas/Abscesses

Hives

Faciale Edema

Atopy

Respiratory disease

Allergic uveitis (Blue Eye)

SEVERE REACTIONS

Vaccine

injection site sarcomas

Anaphylaxis

Arthritis, polyarthritis

HOD hypertrophy osteodystrophy

Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia

Immune Mediated Thrombocytopenia (IMTP)

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (Neonatal Isoerythrolysis)

Thyroiditis

Glomerulonephritis

Disease or enhanced disease which the vaccine was designed to prevent

Myocarditis

Post vaccinal Encephalitis or polyneuritis

Seizures

Abortion, congenital anomalies, embryonic/fetal death, failure to conceive

These are the unfortunate risks pet owners assume when choosing to vaccinate. These risks make it critical to evaluate every vaccine that goes into our dogs, to make certain that no unnecessary vaccines are ever given.

In the next section, we’ll learn how foreign proteins in vaccines can cause allergies and autoimmune disease.

Autoimmunity and the Inflammatory Response to Vaccines Collapse

Disease micro-organisms are often cultured on animal tissue including embryonic chickens or cow fetuses. When a vaccine is manufactured, it’s impossible to divide the wanted virus from the unwanted animal tissue, so it all gets ground up together and injected into your dog’s body.

If a dog eats animal flesh or an egg, it is digested (broken down) into simpler amino acids before entering the bloodstream. The digestive process in most cases changes protein molecules so they don’t trigger an immune reaction.

When foreign animal protein is injected undigested, directly into the bloodstream, it immediately circulates throughout the body. When the body detects the presence of these foreign proteins, an immune response is triggered. Killer T cells are then sent out to consume the cells containing the foreign proteins and protein fragments.

Immunologist Tetyana Obukhanych PhD explains,

I believe that the exposure to yeast, egg, animal, or human proteins in the context of immunogenic (antibody producing) stimuli has the potential to result in sensitization to these proteins or even to break human immunologic tolerance to “self.” The latter is especially relevant to infants, since their immune system is only starting to make the distinction between “self” and “foreign.” Setting this distinction the wrong way from the start, in my view, is likely to pave the road to allergic or autoimmune manifestations.

In the next lesson, we’ll look at how vaccines can suppress the immune system.

Immune Suppression Collapse

The immune system is a finite resource and can only be stretched so far - so it is safest to avoid giving multiple antigens in one vaccine (Moore et al, JAVMA, 2005).

The Canine Adenovirus-2 (CAV-2) vaccine has been shown to cause immunosuppression in puppies for ten days after vaccination (Phillips et al, Can J Vet Res 1989), and the Parvovirus and Distemper vaccines have shown similar results

When vaccines are given in a combination shot, then the immunosuppression is compounded. Veterinary vaccines normally contain anywhere from three (Distemper-Adenovirus-Parvovirus) to seven components. Other vaccines like rabies, Lyme, leptospirosis or bordetella may also be given at the same time, resulting in even further immunosuppression.

Dr HH Fudenberg, a world renowned immunologist with hundreds of publications to his credit, comments

“One vaccine decreases cell-mediated immunity by 50%, two vaccines by 70%…all triple vaccines (Distemper-Adenovirus-Parvovirus) markedly impair cell-mediated immunity, which predisposes to recurrent viral infections, especially otitis media, as well as yeast and fungi infections.”

Similar results were also seen in the 2005 Purdue study referenced earlier. They found that the risk of reactions increased by 27 percent for each additional vaccine given per office visit in dogs under 22 pounds, and by 12 percent in dogs over 22 pounds.

Clearly, vaccination presents risks along with any benefits. In the next section, we’ll take a look at why dogs are over-vaccinated.

Why Dogs Are Over-Vaccinated

Revaccination Schedules Collapse

As we’ve learned, when animals (and humans) are exposed to disease naturally, the immune system is capable of creating a lifetime of protection by filing that information away in memory cells. It's very likely that vaccines offer the same duration of immunity.

But long term studies are expensive, so the vaccine manufacturers originally tested their products for only a few months and subsequently guaranteed their product to last a year.

Vets followed the vaccine label and began vaccinating annually, even though there was no science showing that vaccines needed to be given more than once or that vaccines provided a duration of immunity that was different than that from natural exposure to the disease. Vets also found that tying vaccines into annual visits got pet owners back into the clinic more often for annual checkups, and vets soon became comfortable with that schedule.

In the late 1970's immunologist Dr Ronald Schultz PhD Dipl ACVIM began research to show just how long those vaccines would actually last. The bulk of his testing was done on the core vaccines: Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus (DAP). Dr Schultz knew that the body had "memory cells" that were capable of detecting and deactivating infectious disease for life and he wanted to find out if vaccines were capable of stimulating those memory cells.

Over the next few decades, Dr Schultz tested over 1,000 dogs and tested every major brand of vaccine. He measured their immunity based on serology (measuring the amount of circulating antibodies), as well as challenge (exposing the dog to the actual virus, as would happen outside the lab).

Here are the results of his research:

Duration of Immunity for Core Vaccines

DISTEMPER

The Distemper vaccine for the Rockborn strain provides at least 7 years of protection while the Onderstepoort Strain provides at least 5 years of protection (this duration was shown with challenge studies; serology shows immunity lasts at least 9 to 15 years.

ADENOVIRUS

The Adenovirus vaccine provides at least 7 years of protection by challenge and at least 9 years of protection with serology.

PARVOVIRUS

The Parvovirus vaccine provides at least 7 years of protection by challenge and serology.

Dr Schultz's work clearly shows that vaccines last much longer than vets originally thought when they began vaccinating yearly. It's important to note that the above durations aren't necessarily how long the vaccines last, but rather the duration of the studies. Like natural infection, Dr Schtulz’s research shows that vaccines are extremely likely to provide many years, if not a lifetime, of protection.

In the next section, we'll take a look at how Dr Schultz’s work influenced today’s revaccination schedules.

Canine Vaccination Guidelines

In 2003, the American Animal Hospital Association Canine Vaccine Task Force evaluated the data from Dr Schultz’s challenge and serological studies and, while noting that the core vaccines had a minimum duration of immunity of at least seven years, compromised in 2003 with the statement that “revaccination every 3 years is considered protective.”

Task force member Dr Richard Ford, Professor of Medicine, North Carolina State University, said that the decision to recommend a three year revaccination schedule for core vaccines was a compromise.

“It’s completely arbitrary…,” he said. “I will say there is no science behind the three-year recommendation…”

Vets were comfortable with annual vaccination and many veterinary clinics relied on the income that annual vaccination generated, so getting them to move away from annual vaccination was proving difficult.

After the 2003 task force however, all of the major veterinary vaccine manufacturers completed their own studies showing a minimum three year duration of immunity on the core vaccines (Distemper, Adenovirus and Parvovirus). So now vets could feel even more comfortable giving vaccines every three years or more, instead of annually.

Dr Schultz continued with his work and by 2006, had performed seven additional studies on over 1,000 dogs and repeated the same results, effectively showing that 95 to 98% of the dogs were protected for much longer than three years and most likely for life.

The Canine Vaccine Guidelines were updated again in February 2007 to update new information about Parvovirus and Distemper vaccination. Nearly thirty years after Dr Schultz’s initial research, the AAHA changed their revaccination recommendations for core vaccines to “revaccination every 3 years or more is considered protective.”

In the meantime, research was increasingly showing the deleterious effects of vaccines and this didn't escape the AAHA’s notice. In 2011, the AAHA updated their Canine Vaccination Guidelines once more. They advised that:

“Among healthy dogs, all commercially available [core] vaccines are expected to induce a sustained protective immune response lasting at least 5 yr. thereafter”

Back in 2003, the AAHA Task Force advised vets of the following in regard to their 3 year recommendation:

“This is supported by a growing body of veterinary information and well-developed epidemiological vigilance in human medicine that indicates immunity induced by vaccination is extremely long lasting and, in most cases, lifelong.”

While Dr Schultz’s work provides overwhelming evidence that the core vaccines can protect for at least seven years, and likely a lifetime, the veterinary associations have been slow to change their revaccination recommendations.

In the next section, we’ll learn how individual vets are responding to Dr Schultz’s work.

Why Dog Owners Need to Understand Duration of Immunity Collapse

Even though most major vaccine manufacturers have completed three year testing on their products, and the AAHA and AVMA state that the core vaccines can protect for at least five years, many vets are still vaccinating too often. In fact, the senior brand manager for vaccine manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim reports that 60% of vets are still vaccinating annually for the core vaccines.

The veterinary text book, Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy XI (Small Animal Practice), has this to say about annual vaccination on page 205:

A practice that was started many years ago and that lacks scientific validity or verification is annual revaccinations. Almost without exception there is no immunologic requirement for annual revaccination.

While many vets are vaccinating less often, the vast majority are still vaccinating too often. This is problematic because, although vaccines can protect companion animals from infectious disease, they are also capable of causing disease and ill health.

In the next section, we'll look at how to protect your dog with as few vaccines as possible.

How To Protect Your Dog With Fewer Vaccinations

Puppy Vaccination Schedules

When puppies are very young, they are protected from disease by ingesting their mother’s first milk, called colostrum. This rich milk contains maternal antibodies against disease, which the mother passes down to her puppies. The puppy’s immune system is not fully mature, or active, until around six months of age, but the maternal antibodies provide passive immunity to each puppy.

When a puppy with a reasonable amount of maternal antibodies is vaccinated, the maternal antibodies will essentially inactivate the vaccine, just as they would a real virus. In a study performed by Vanguard, researchers found that a combination vaccine (which typically contains Parvovirus, Distemper and one to five other antigens), given to six week old puppies had only a 52% chance of protecting them against Parvovirus.

This means that the puppy vaccinated at six weeks of age has 100% of the risk of the vaccine but only a 50% chance of being protected.

At nine weeks of age, 88% of the puppies in the study showed a response to the vaccine.

At 12 weeks, 100% of the puppies were protected. Some vaccines will provide protection earlier or later.

Dr Ronald Schultz has come to the following conclusion, based on his research:

“Only one dose of the modified-live canine ‘core’ vaccine, when administered at 16 weeks or older, will provide long lasting (many years to a lifetime) immunity in a very high percentage of animals.”

That very high percentage is 92% to 95% of dogs.

Vaccinating puppies under 12 weeks of age, and certainly under nine weeks of age is a high risk, low reward approach. Not only is the vaccine less likely to provide immunity, but it will also suppress the puppy’s immune system for ten days afterward.

Why Puppies (and Dogs) Don’t Need Boosters

Pfizer performed an interesting field study in 1996 where they split vaccinated puppies into two groups. Group A received a single vaccination at 12 weeks and Group B received a first vaccine between eight to 10 weeks, and a second at 12 weeks.

When titers were measured, 100% of the puppies vaccinated once at 12 weeks were protected whereas only 94% of the puppies in Group B were protected – despite receiving two vaccines as opposed to one.

It appears that the first vaccine can interfere with the second vaccine. So vaccinating your puppy twice not only doubles his risk for adverse vaccine reactions, it appears to make vaccination less effective overall.

Most people – and many vets – believe that it takes more than one vaccine to create immunity in a puppy. This simply isn’t true. It only takes one vaccine to protect a puppy, and if it is given at or after 16 weeks of age, it should protect him for life.

Maternal Antibodies

The only reason vets give puppies a series of vaccines is because they don’t know when the maternal antibodies will stop blocking the vaccine. The point in time when the maternal antibodies wane can vary between eight weeks and 26 weeks. So vets vaccinate every two to four weeks, trying to catch the window of opportunity when the maternal antibodies are low enough for the vaccine to work.

Most vets also vaccinate once more at a year of age – just to be certain. Nearly all vets vaccinate every year or three years after that – yet as Dr Schultz states, there is no need for revaccination once a puppy is protected – and if a puppy receives a vaccination at or after 16 weeks of age, he is very, very likely to be protected for at least seven years after, and likely for life.

Puppy Shots

Most vets vaccinate puppies every two to three weeks, because they have no way to tell whether the maternal antibodies have blocked the vaccine. We now know that the more vaccines we give our dogs, the more we expose them to mercury, aluminum and other toxins which are not only dangerous for the developing puppy’s neural system, but can be responsible for the common diseases we see in dogs today.

In place of revaccinating puppies at regular intervals, you can do two things to reduce the number of vaccines given to your puppy.

First, you can vaccinate only once at 16 weeks of age. Since we know that puppies vaccinated at this age are extremely likely to be protected for life, it would make the most sense to wait until this age to vaccinate. Since even vaccinated puppies should stay away from dog parks and other heavily trafficked areas (and the vet’s office should be included in this list), waiting until 16 weeks of age to vaccinate is a safe choice for most healthy puppies.

Shelters and Rescues

Many puppies are in high risk areas like shelters or rescues. Some puppies also come already vaccinated at 6 or 8 weeks of age. For puppies who are vaccinated at an earlier age, and even puppies vaccinated once at 16 weeks of age, titer tests can be invaluable.

In the next lesson, we’ll show you how this simple test can tell you if your dog needs another vaccination.

Non-Core Vaccines

Knowing The Difference

By Catherine O'Driscoll

Many of the vaccines vets use on your dog are categorized as core or non-core.

The core vaccines include parvovirus, distemper, adenovirus (canine hepatitis) and rabies. These vaccines all protect against viruses, which are easy to protect dogs against. In fact, viral vaccines are so effective that, when given to a dog over four months of age, they’ve been scientifically proven to protect that dog for years, and most likely for life.

The non-core vaccines aren’t in included in this group for three main reasons:

- They don’t work as well

- They don’t protect for very long

- They’re more dangerous

Leptospirosis

The majority of dogs with known leptospirosis have been found to be without symptoms – they live with it without getting ill.

This isn’t to say that leptospirosis can’t cause illness in dogs. In some cases lepto can be fatal.

However, in the 1996 Canine Health Concern vaccine survey 100% of dogs with leptospirosis had been vaccinated within three months prior to infection. This can only be because:

- The vaccine caused the disease, or

- The vaccine didn’t contain the serovar that caused the illness, or

- The vaccine contained a non-local serovar that the dog hadn’t adapted to, or it just didn’t work.